Interview with Loren Glass

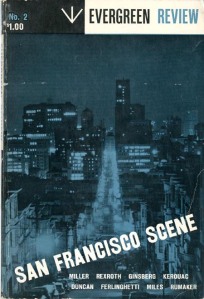

One of our inspirations here at Contrappasso is the Evergreen Review, the classic journal published by Barney Rosset’s Grove Press from 1957-1973, and revived online since 1998.

This week I traded a few emails with Loren Glass, Associate Professor of English and the Center for the Book at the University of Iowa, to discuss his exciting new book, Counter-Culture Colophon: Grove Press, the Evergreen Review, and the Incorporation of the Avant-Garde (Stanford University Press).

Loren Glass

*

MATTHEW ASPREY: When did you first become aware of Grove Press and the Evergreen Review?

LOREN GLASS: I was researching a project on modernism and obscenity and became aware of Grove’s centrality to the post-war campaign against censorship in the US.

So how did you come to write Counter-Culture Colophon? What was the research process?

I went to the Grove Press papers at Syracuse University Special Collections library to look into their materials related to the trials of Lady Chatterley’s Lover, Tropic of Cancer, and Naked Lunch. I quickly saw that there was a much larger story, one which looked more fascinating and more important than the project on obscenity that I was envisioning. I spent a total of about two months over a period of two years with that archive. I also did research in the Donald Allen Papers at UC San Diego and with Barney Rosset’s Papers at Columbia. I interviewed Barney twice, as well as Fred Jordan, Nat Sobel, Morrie Goldfischer, Herman Graf, Claudia Menza, and Judith Schmidt Duow.

Barney Rosset seemed prepared to risk all financially to further his political and literary objectives. Can you tell us about his vision for society, why he was ultimately so important as a publisher, and why he was left in reduced circumstances in retirement?

I see Barney as a romantic revolutionary. For him it was all about “sex and politics,” as he repeatedly said. He was more of a contrarian than a visionary, a sort of left-wing libertarian determined to fight the powers that be but without any carefully articulated idea of what would come next. In terms of his importance, he was in the right place (NYC) at the right time to really make a difference. A combination of factors—the paperback revolution, the expansion of the American university, the weakening of censorship—converged to make his efforts at Grove particularly successful. However, once the cultural revolution he set in motion had succeeded, he became less relevant, and the corporate consolidation of publishing made it more difficult to run a company as recklessly as he did. He put all his money into Grove, and was barely able to cover his debts when he sold it.

Daniel O’Connor and Neil Ortenberg’s documentary Obscene: A Portrait of Barney Rossett and Grove Press was released in 2007. It seemed long overdue. Have Barney Rosset and Grove Press otherwise been given their due recognition?

I would say, emphatically, no. I was astonished that there hadn’t been a book on Grove. Part of the reason is that they did so much, far more than is covered in the film, or even in my book, though I try to be comprehensive.

The Olympia Press in Paris had a close association with Grove. Olympia’s publisher Maurice Girodias was a colourful character and a dubious businessman. You write about how Barney would eventually come to support him financially. What was their relationship?

Barney called it “deep.” Dick Seaver called it “a fragile friendship.” I think they had similar characters in certain ways, but Barney had more access to money and was also a better businessman. Girodias was notoriously sloppy with contracts and copyrights, and Barney basically cannibalized his entire catalogue.

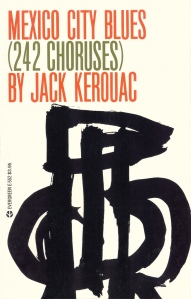

I love the graphic design of Roy Kuhlman for Grove Press in its classic era. His covers were an endlessly inventive commercial application of mid-century Modernism, as impressive as the work of Reid Miles for Blue Note Records. Sadly there does not seem to be a book in existence celebrating that relationship – or even about his work in general. How important was Kuhlman to Grove?

Kuhlman was central, absolutely, to establishing Grove’s brand recognition, and he was the first book artist to incorporate Abstract Expressionism into cover design. His daughter, Arden Riordan, is apparently working on a book dedicated to his work. There’s also an amazing website dedicated to his work with Grove: www.uncoveredgrove.com

There are rumours Barney Rosset wrote a memoir before his death. Are we likely to see that published?

Barney’s memoirs are being edited by Bradford Morrow for Algonquin. Rumor has it that he doesn’t say enough about Grove, but rather focuses on his years in China, though I haven’t read the manuscript.

*

More information on Counter-Culture Colophon is at Stanford University Press.

Read Loren Glass’s recent two-part feature on Grove at the Los Angeles Review of Books (parts I and II).