Our celebration of British author Clive Sinclair continues. Here’s a gallery of Sinclair’s books.

Contrappasso 2 features a long career-spanning interview and Sinclair’s never-before-published novella STR82ANL.

Our celebration of British author Clive Sinclair continues. Here’s a gallery of Sinclair’s books.

Contrappasso 2 features a long career-spanning interview and Sinclair’s never-before-published novella STR82ANL.

Who says there are no literary schools in Australia?

Here’s a close-knit group of Sydney writers, many past or future Contrappasso contributors, a cross-generational literary school known around town as the School Bus Gang.

Left to right: Clinton Walker, Vanessa Berry, Peter Doyle, Matthew Asprey, and Raymond Devitt.

Photo credit: Simon Yates.

Our friends at the Los Angeles Review of Books have taken first dibs on the online publication of ‘El Hombre Valeroso’, our expansive interview with British author Clive Sinclair.

The interview, conducted by Matthew Asprey, originally appeared in Contrappasso issue #2. The LARB had this to say:

ONE OF THE GREAT PLEASURES for us at Los Angeles Review of Books has been the opportunity afforded for serial discovery. In this case, of the extraordinary English writer Clive Sinclair, whose bibliography betrays the influence of everyone from Nabokov to John Ford, but also of the splendid quarterly Contrappasso, a periodical that — like Sinclair — moves restlessly, thrillingly among its interests and concerns. From neglected masters like Floyd Salas and James Crumley, to less-neglected ones like David Thomson and Elmore Leonard, the Sydney-based Contrappasso publishes international writing of the highest order. We are pleased to present Contrappasso editor Matthew Asprey’s interview with Clive Sinclair, below, and encourage you to visit contrappassomag.wordpress.com to discover more.

‘El Hombre Valeroso’ begins:

CLIVE SINCLAIR was born in England in 1948. He is a recipient of the Somerset Maugham Award, the Jewish Quarterly Prize, and the PEN Silver Pen Award for Fiction. He holds a doctorate from the University of East Anglia and is a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature.

Sinclair’s novels include Blood Libels (1985), Cosmetic Effects (1989), and Meet the Wife (2002); his stories have been collected in Hearts of Gold (1979), Bedbugs (1982), and The Lady with the Laptop (1996). Sinclair’s most recent book is True Tales of the Wild West (2008), an experiment in the new genre of “dodgy realism.”

The following interview is based on a transcript of a conversation I had with Sinclair at his home in London in early 2011. More than a year later, the raw transcript was edited and restructured, supplemented by further questions and answers by email, and finally revised by interviewer and interviewee.

MATTHEW ASPREY: Your first book, Bibliosexuality (1973), is a very obscure title. I’ve never seen a copy. Do you want to tell me anything about it?

CLIVE SINCLAIR: I’d rather not but, since I can see the thumbscrews bulging in your pockets, I’ll oblige. The title is a neologism, of which I remain rather proud, and look forward to one day seeing housed in the OED. Bibliosexuality describes a disorder of the senses in which a perverse relationship with a book is not only desired, but also achieved. In short, the novel offered the world of letters as a substitute for the real thing. The main influence on it would be my time at the University of East Anglia, where I encountered the likes of Malcolm Bradbury, Angus Wilson, Jonathan Raban, and the Sages — Lorna and Victor. I had no idea what I was getting into. I went there in a completely arbitrary fashion and as a complete innocent. The aforementioned practiced what was then called New Criticism, which insisted that the text be examined as an artifact entire unto itself. The very opposite of structuralism, unknown (at least to me) at the time. You — the critic — ask about the author’s intentions and intentionality. For example, that yellow vase on the shelf. Why yellow? You assume everything is there for an artistic purpose. The book that I produced as a consequence was immensely self-conscious. Of course it was heavily influenced by Nabokov. It was full of linguistic resonance and also the sex element, to put it roughly. Portnoy’s Complaint had just come out in 1969. So it was a mishmash of influences. It could have been brilliant. It wasn’t, but it could have been.

MA: How old were you?

CS: Twenty-one when I wrote it….

Read the complete interview at the Los Angeles Review of Books

or in issue 2 of Contrappasso Magazine, available in Paperback, Kindle Ebook, or other Ebook formats @ Smashwords.

ON THE BIRTH OF RAYLAN GIVENS

from ‘In Australia: An Interview With Elmore Leonard’ by Anthony May (Contrappasso #2, December 2012)

Date: 21st February, 1994

Location: 3rd floor lobby, Ritz-Carlton Hotel, 93 Macquarie Street, Sydney.

MAY: Although you start the novel [Pronto, 1993] with Harry, it’s actually Raylan’s novel as much as anyone’s. Who was the original hero?

LEONARD: Harry. I thought that Harry would take it all the way. Then Harry got to Italy and he changed. I mean, I didn’t change him. He changed. This is the way it works out. He gets there in December and it’s cold. When I was there it was towards the end of November and places were starting to close up. I could imagine what it would be like in the summer or even in the fall and everything’s going, everyone’s on the beach. And that’s the way it would have been on his previous trips. Now he gets there and it’s like a different place. He’s got this building that’s got this probably 300 year old leak in the ceiling and it’s just not the same. He can’t be Harry in this place. He meets this woman and he’s talking to the woman and he doesn’t get along with her. He picks her up and he just wants to get rid of her. And she doesn’t see anything in him. He doesn’t entertain her at all. It just doesn’t seem to work. And I thought what am I going to do here? He needs help. I thought, in this frame of mind he’s going to start drinking again and he’s going to get deeper into trouble, more disenchanted with the place.

Now the idea of course was that Raylan was going to get there. I went back a little bit and changed Raylan’s original home from Western Kentucky to Eastern Kentucky to the coal mines. I had to give him a background of having been familiar with violence beyond what he might have seen as a marshal. And Harlan County, I’d been wanting to use Harlan County anyway and got hold of that documentary that won an Oscar about twenty years ago called, Harlan County USA. Bloody Harlan, that’s what it’s known as. That helped me enormously. I got to know him then. I had my researcher look up all kinds of things, not only that movie but he also got me news magazine and newspaper stories about the strike and that time, the early seventies. There was a picture in one of the newspaper stories of a marching band, a high school marching band practising, they didn’t have their uniforms on. Where do they go to school, because Raylan went to that school. The caption said that they’re in Everetts, Kentucky, a coal mining camp. So then I call my researcher and find out what they’re known as, the warriors or whatever, and what the school colours are, and what the Harlan high school colours are, what they’re called and so on. Just little things like that, I think add to it.

*

LEONARD: The book I’m doing now [Riding The Rap, 1995], I’m bringing back Raylan. Pronto was optioned but I have it in the contract that I can use Raylan again, that they’re not going to own Raylan. There was a little fight there. I said, well, do you want Pronto or not, because I’m not going to sell it to you unless I can keep Raylan for myself. I want to use him again. And Harry’s in it, and Joyce to some extent. I begin with Raylan wishing that Harry would disappear because he’s as childish as he was at the end of the book and he’s drinking again, heavily. He’s lost his license, drunk driving, and he relies on Joyce to drive him around, although he does drive himself too. And he’s feeling sorry for himself and Raylan wishes he’d disappear. And he does. They don’t know where he went. They’re sure he didn’t go back to Italy because he would have made a big to-do about it. He wouldn’t have just slipped away in the night.

It was funny on this book tour, the one I’ve just done in the States, people asked me, ‘Whatever happened to Dale Crowe, jnr.? He took off in that Cadillac and what happened to him?’ Because he didn’t come back into the book (Maximum Bob) and a lot of people thought he was going to be important to the story seeing as it opens with him. I said, ‘I don’t know, he’s probably driving around in the Cadillac, he’ll get caught. Why not, he’s a dumb kid.’ But just the fact that people asked me about him, I had opened the new one with Raylan talking to a psychic. He knew Harry had talked with this psychic and the psychic was possibly the last person who saw him, at least that anyone knows about. So he goes to see the psychic, not to know anything about himself but to find out about Harry. But the psychic tells him things about himself. I thought, This is a good opening. I like this opening. But there was certainly a scene with Harry and the psychic and if I open with Raylan then I’m going to have to just tell about Harry and the psychic or else flashback. I don’t want to flashback. So somebody has to talk about it, the psychic and somebody else. Why did Harry go to see the psychic? I finally realise that I’m not going to be able to open with Raylan and the psychic. I have to open with something else. And something else and something else until finally Raylan and the psychic is chapter seven.

So I’ve got these other chapters going, I thought, I gotta open with Raylan, he’s my main character and I’m gonna be true to him this time. And then I remembered the people asking me about Dale Crowe. So I opened with Ocala police. Ocala’s a city in Florida state, Ocala police picked up Dale Crowe for weaving and having a broken tail light. They bring him in. They give him a breathalyzer test and then look him up on the crime computer and find out that he’s a wanted fugitive. So then in the next paragraph, Raylan comes to pick him up. Raylan then lets Dale Crowe drive back to Palm Beach County and in their dialogue, you find out some of the things that have happened since Pronto. I thought, That’s the way to get this exposition out of the way. Dale Crowe, jnr. really doesn’t know what he’s talking about, nor does it matter. Nor does he understand why he’s being told this, and yet there is a point in Raylan telling him. He thinks Dale Crowe is a punk kid and there is something in his story about Harry and Joyce that could apply to Dale in a way. Then Dale tries to get away. He tries to hit him but Raylan knows that Dale’s going to try this. As Dale Crowe swings at him, he pops him right in the face with his cowboy boot and then handcuffs him to the steering wheel. Then when they get into town, they get to West Palm, they get off the turnpike and they’re into West Palm, a car hits them from behind. It pops the trunk a little bit so Raylan gets out and goes back and he sees this pickup truck. Two black guys get out of the pickup truck and one of them’s got a gun and it’s a car jacking. The guy says, We’re gonna trade you our truck for your Cadillac. The Cadillac that he was using was a confiscated drug car. So the one black guy goes up to get in the car and get Dale out. Then he calls to his friend and says, Hey, come here. As the guy walks up there, Raylan opens the trunk and gets his shotgun out. He steps over into the road and then he racks the pump, which every lawman knows will get more attention and respect than anything else. And they turn around and there it is, they’re looking at a shotgun. He says, I’ll give you guys some advice, don’t try and jack a car that’s being used to transport a federal prisoner.

MAY: The psychic isn’t Maximum Bob Gibbs wife, is it?

LEONARD: No, but originally I thought that she could be in it. There’s a town north of Orlando called Cassadaga where nearly everyone who lives in the town is a psychic or a clairvoyant or in the spiritualist church. It’s just a county road, and on one side of the road are all the legitimate psychics who are in the spiritualist church. On the other side are the ones who come along because these people had made this area so popular. People come from all over to get readings. So on the other side are a lot of fortune tellers, pseudo-clairvoyants, tarot card readers and so on. And that’s the whole town, that’s it. It’s an unusual town. I was going to use Cassadaga. I was going to set most of the book there but there wasn’t enough to it. I need more bright lights, big city. So I moved my psychic out of there down further into South Florida. Her name is Reverend Dawn Navarro. She’s about 28 years old, she’s good looking and you’re not sure if she really is psychic or not. Except that she tells things to Raylan that he relates later to Joyce that make him wonder if he might have said something. ‘The fact is she knew I was a coalminer from Kentucky, I might have said something.’ Then she calls somebody else. She says, ‘There’s a guy here looking for Harry Arno and he’s a federal officer.’ And the guy she’s talking to says, ‘What kind of a federal officer?’ She says, ‘I don’t know.’ He says, ‘What do you mean, didn’t he show you his I.D., his credentials? Why do you say he’s a federal officer?’ She says, ‘He is, that’s why.’ And at the end of their conversation, she says, ‘He shot someone.’ He says, ‘well, what, he told you about that?’ She says, ‘No.’ She was reading him using psychometry where she holds his hand. She says, ‘No, I felt the hand that held the gun.’

Anthony May’s complete 65-page interview series with Elmore Leonard is available in Contrappasso issue #2, available in Paperback, Kindle Ebook, or other Ebook formats @ Smashwords.

ON CLINT EASTWOOD, BRUCE WILLIS, AND WILLIAM FRIEDKIN

from ‘Doing What I Do: An Interview With Elmore Leonard’ by Anthony May (Contrappasso #2, December 2012)

Dates: 1st-3rd July, 1991

Location: Elmore Leonard’s home in Birmingham, Michigan. The interview took place in Leonard’s study across his writing desk.

MAY: When you made that move from westerns to crime fiction, there’s a series of books that you do, Big Bounce [1969], Moonshine War [1969], before you move into that City Primeval world. Mr. Majestyk is also around that period isn’t it?

LEONARD: Yeah, early ‘70’s, original screenplay.

MAY: I was just reading the other day about that, actually. I was reading the Barry Gifford collection, The Devil Thumbs A Ride. He describes Mr. Majestyk as a ‘melon western’, as opposed to a spaghetti western, but does so quite affectionately, I think.

LEONARD: I took Mr. Majestyk from The Big Bounce and named the character, it’s a different guy completely, y’know. But I figured, I need a title, and I know Mr. Majestyk is a good title, and I figured, well, nobody’s read The Big Bounce. I’ll just use that name. Originally, this story was meant for Clint Eastwood. He had called up and said he wanted something new. I had written Joe Kidd, an original, for him. It was shot but not yet released. And he called up and said, Dirty Harry is making a lot of money everywhere, but he only had a few points in it, I gathered. Now he wanted to own his next property. What he wanted really was another Dirty Harry but different. And so I thought of Mr. Majestyk and I called him the next day and told him about a melon grower, just basically the situation, I’d just thought of it that minute. And he called back that night or rather just a little later that night and said he wasn’t seeing him as a melon grower, rather an artichoke farmer because artichokes were grown not far from where he lived.

*

LEONARD: The trouble with…Bruce Willis’s screenplay that he gave me of Bandits—I read it and I spoke to him and I said, ‘This guy doesn’t understand, if you want to play yourself that’s one thing, with all this smart aleck stuff. If you wanna do that then it’s quite a different character.’ He said, ‘Yes, yes, I understand.’ I said, ‘Well, look at this line for example, when Delaney’s in the bar and he’s talking to this woman who’s got bruises on her, a go-go dancer. She walks away and he says to his friend, the ex-cop, “y’know every sixteen seconds in the United States a woman is physically abused?” And the bartender says, “you wouldn’t think so many women would get outta line.”’ Now, in the script he delivers the line and then, direction, grins and winks. I said, ‘No, he doesn’t grin, this is the guy’s mentality. Don’t tell the audience anything. If the audience thinks that’s fine, let ‘em laugh. Don’t tell ‘em anything.’ It’s like television, holding up applause cards.

MAY: So Willis is actually going to do the screenplay himself?

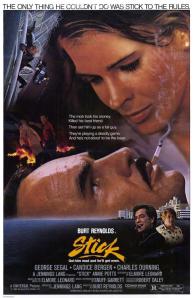

LEONARD: Oh, no. He had it done by the guy who rewrote Stick.

MAY: Oh, no!

LEONARD: Well, I haven’t seen it apart from those couple of scenes. It’s also the same guy who did Sudden Impact and City Heat, Joseph Stinson.

MAY: If I remember right, with Stick, they change the dialogue around. They take some lines from Barry Stamm, the millionaire character [George Segal], and give them to Burt Reynolds [as Stick] so the lead gets all the good lines. Reynolds gets to say the funny lines.

*

from ‘In Australia: An Interview With Elmore Leonard’ by Anthony May (Contrappasso #2, December 2012)

Date: 21st February, 1994

Location: 3rd floor lobby, Ritz-Carlton Hotel, 93 Macquarie Street, Sydney.

LEONARD: I did a script, did I tell you, last year with Billy Friedkin. Paramount had asked me to rewrite a script they had that was not unlike Basic Instinct, which had, that week, made $155 million gross. They had one kinda like it where a cop falls in love with a woman who’s involved in crime. And I said, no I don’t want to do it. But Friedkin was involved and he called and said, ‘Why don’t we do our own?’ So we talked it out over the phone and I wrote one set in Florida. He liked the idea, but he said, ‘I don’t like all these Cubans. Get rid of the Cubans. And the money laundering, and cocaine.’ Well, there was no cocaine in it but the money came from cocaine. There’s a guy who was laundering money for the Cubans and he has money sitting in his house at a particular time and by morning it won’t be there. There’s two and a half million dollars or something that he will send somewhere and by the time it comes back and gets into some land development it’s been cleaned and pressed. So he didn’t like that. He said, ‘Get rid of the Cubans and the money laundering.’ So I got rid of that. No, I didn’t get rid of the Cubans. Oh, and he said, ‘Play down the cop.’ Even though the cop was supposed to be falling in love with the woman. So I added a burglar. A burglar was in the house the night when these guys were with the woman, it’s an inside job, she opens the door for the guys to come in and pick up the money. But there happens to be a burglar in the house that night who we have met just before, posed as a carpet cleaner going through the house to see what he wanted and to unlock a window or something, a French door. So that he’s in the house when all this happens. Friedkin likes the burglar, he likes the girl, he likes the bad guy that comes in to get the money, but he doesn’t like the Cubans. ‘Get rid of the Cubans and the money laundering.’

So I went up to see him but in the meantime he’s married Sherry Lansing. Right in the middle of this deal [Brandon] Tartikoff leaves as Head of Production and Friedkin’s wife comes in as Head of Production. I said, ‘What happens to our deal now?’ They said, ‘Are you kidding, his wife’s running the studio!’ So I said, ‘Here’s the problem, here’s this guy, who’s kind of a wealthy guy, but if he’s not laundering money, what’s he doing with two or three million bucks sitting there in his house, cash?’ And Friedkin said, ‘Let’s think about it.’ I said, ‘My least favourite thing to do is to sit with someone and plot, why don’t I call you?’ So I left and my agent, Michael Siegel said, ‘Why don’t you just forget about it? You’ve gotten paid up to date, you’ve made enough money on this thing. Go write your book.’ I said, ‘I’m gonna give it three hours and see if I could think of why the money would be sitting there.’ So, back to the hotel. The next morning I woke up at five o’clock and I was gonna give it three hours. I was gonna read but I decided to just think instead. And it came in five minutes. Then I had to wait three hours to call Friedkin. So I called him up and I said, ‘There’s a televangelist who uses ESP powers. Open with him. He’s healing this little girl who stutters and he’s trying to get this little girl to say, “Praise Jesus”. And she can’t say it. So he lays his hands on her and does all this stuff. And she says, “Praise Jesus”. And there’s a collection. And the camera watches where the money goes. Some of it goes out to his limo. And the limo goes home and then you see the bag of money go in. There’s the money.’ He says, ‘I love it! Write it!’ It took about three weeks and I sent it to him. In the meantime he has started production on Blue Chips, a basketball picture. So I haven’t heard from him since then.

MAY: And what was that going to be called?

LEONARD: I had a good title for it too, Stinger. The guy who engineers this scam, the heist, is a fishing guy out on Lake Okeechobee and he designs fishing lures. And one of his lures is a stinger. And there’s some reference to the girl as a stinger. She’s the lure. He’s finished with Blue Chips which opened last week in the States but now I hear that he’s doing something with Peter Blatty, the Exorcist guy. So it’s OK with me. There’s so much of that done. They pay a lot of money for a script that just never gets off the shelf. But this is different. I used to write scripts like that for fifty thousand, a hundred thousand. This is six hundred thousand bucks and it’s just sitting there. They don’t care.

More extracts from Anthony May’s Elmore Leonard interviews will appear all week. The complete 65-page interview is available in Contrappasso issue #2, available in Paperback, Kindle Ebook, or other Ebook formats @ Smashwords.

ON RESEARCH

from ‘Doing What I Do: An Interview With Elmore Leonard’ by Anthony May (Contrappasso #2, December 2012)

Dates: 1st-3rd July, 1991

Location: Elmore Leonard’s home in Birmingham, Michigan. The interview took place in Leonard’s study across his writing desk.

MAY: We were talking earlier about the time before you started working with Gregg Sutter, and the research that you used to do for yourself. Were there any sorts of reference books that were useful or was that done from more contingent sources, like you said about picking up material off MTV? Did you have any books that you would go to like crime reports or things like that? Did they help?

LEONARD: No, just the paper. The first time I did the piece for the Detroit News, ‘Impressions of Murder’ [1978], I had not done any research directly with the police. I had with newspapermen, like the crime reporter who took me to the morgue, a crime reporter who dealt with the cops. But I didn’t get into the details of procedures. I think the only research for the most part that I did outside of using settings around Detroit that I knew of or would visit was going to the library. If you look at my research boxes, you’ll see they are envelopes from the early books up to a box or two boxes for Killshot. I’ll show you what I have.

MAY: You’ve got notebooks and rolls of film…

LEONARD: I would never go to all this trouble myself. This one is all full of Bail Bondsman News. These are all newspaper pieces about bail bondsmen. This one, I think this one is a tape of ‘Demonstrations of Machine Guns’ and the voice-over tells what the guy’s firing, its rate of fire, the kind of cartridge it uses and all that. So I went through that one and I picked out maybe six or eight machine guns with a few facts and I described a movie that the character in the book had bought at a gun show. And he shows this to his customers who come from Columbia, Detroit and New York. He shows them this movie, you want an Uzi, you wanna TEC-9 and all that. And he sells them on it, see. He tells them how much. [Skipping through research box] Here’s some material on bounty hunters. Bounty hunters sometimes are hired by bail bondsmen.

MAY: And you get to read books like Gunrunning For Fun And Profit? So Gregg Sutter goes down and gathers all this material for you?

LEONARD: Yeah. These are parts of manuscripts. These are interviews with bail bondsmen. Mike Sandy, he’s the guy in the movie. This is the ATF file. This is the eating area [Looking at floorplan of a mall—a location in Rum Punch]. The food service area in the mall. I have about one, two, three scenes which take place in there. I would have never gone to this trouble before, before I had a researcher.

MAY: Presumably different aspects of this research feed into different things. I mean, some of it’s for detail and some of it’s for visualisation.

LEONARD: Yeah. [Still searching boxes] A letter from Medellín, drug capital of the world. So I took a few facts out of that and I have Ordell, the gun dealer, telling the jack boys—he has some young black guys working for him, in Florida, and they are called jack boys—who knock over street dealers and dope houses that love to go into the salt waters and shoot the place up and steal everything. So he’s got these young 18, 19 year old jack boys working for him and he tells them about the boys down in Medellín who are called pisto-locos, who are that version of the Columbian jack boys, and how many of them get killed each year and how they should be so happy that they were born in America.

MAY: A much healthier business to be in here.

LEONARD: Yeah. So I already know how I’m gonna use that material. This is where I break down the paragraphs once I get into the book just to help me find things when I look back.

MAY: This notebook? Does Chili Palmer come back in Rum Punch?

LEONARD: No, but I was considering that.

MAY: Has this complicated things at all, having this amount of material to draw on, or does it make life so much easier?

LEONARD: Oh, much easier. But I don’t have it all at once. All these things didn’t come until the very end. In fact, I thought all my research was finished then I decided I was gonna have more scenes in this big mall than I had originally. And Gregg Sutter was down there, he had gone down there for some reason, so I said, ‘take me some pictures’ and he called the Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms agent, who’s part of the Treasury, and asked him a question, some technical thing that had to do with where I was up to in the book.

MAY: And that produces more stuff?

LEONARD: Yeah, right.

MAY: It seems to be such a different job researching this material from researching the westerns.

LEONARD: Oh, yeah. The westerns, what did I use? I did them with this, The Look of the Old West by Foster Harris. I would use just an old catalogue of westerns. And I used my Arizona Highways. I relied on Arizona Highways for my descriptions. I’d find a canyon or something, the kind I want, and then the caption would tell you what kind of rock it was and so on. It’s better than being there. Because when you’re out there you wouldn’t know if that was one kind of rock or another, you know. So using Arizona Highways, that worked.

More extracts from Anthony May’s Elmore Leonard interviews will appear all week. The complete 65-page interview is available in Contrappasso issue #2, available in Paperback, Kindle Ebook, or other Ebook formats @ Smashwords.

ON KILLSHOT AND DETROIT

from ‘Doing What I Do: An Interview With Elmore Leonard’ by Anthony May (Contrappasso #2, December 2012)

Dates: 1st-3rd July, 1991

Location: Elmore Leonard’s home in Birmingham, Michigan. The interview took place in Leonard’s study across his writing desk.

MAY: And it’s interesting that you’ve located yourself around Detroit. Just yesterday, as we were driving around the downtown, I thought your novelistic descriptions of Detroit were almost like a guide book to the city. Streets connect, places are there. Do you find that’s more difficult to do when you are dealing with other cities, with Miami or the New Orleans of Bandits [1987]?

LEONARD: No. It’s not more difficult because I find out what neighborhoods I’m gonna use and I study maps. I was always referring to this particular map when doing Rum Punch and Maximum Bob. West Palm, Palm Beach, Palm Beach Shores.

MAY: You say that you don’t think of yourself in that tradition of Chandler and Hammett but that writing is always located within a city.

LEONARD: But if we had lived in Buffalo, then there’s still crime in Buffalo. I didn’t pick Detroit in particular. Some people think I chose Detroit because it was, at the time, the murder capital of the US and it has a reputation. In the movies they were always sending away to Detroit to get a hit man.

I think you can use any place, any place. In Killshot I was gonna make the Blackbird pure French-Canadian. Then I decided it would be too hard to handle his accent all the way through. So instead of being from Montreal he’s from Toronto and he’s half Ojibway Indian. But the idea for his character came from a documentary I saw probably six or seven years ago. It was done in 1979 about the Mafia in Montreal. The filmmakers would run down the street with their mikes trying to interview Mafia figures, y’know, and in one segment you see these two tough guys coming along and they stop ‘em with their mikes and these are the Dubois brothers. And the Dubois brothers think all the Mafia guys are punks. And they’re really tough guys. No respect for, no fear of the Mafia at all. And I thought, I want one of those Dubois brothers. But I gotta change him in order to handle him for 90,000 words.

MAY: I think it works really well in Killshot. Killshot is one of my personal favourites because I think you hit the tone with the husband and wife humour that’s just terrific. But, before I want to talk about that, I want to ask you about the strategy of having two contrasting baddies, baddies that contrast so greatly as Armand and Ritchie do.

LEONARD: Wayne, the ironworker, was gonna be the main character in Killshot but it was so obvious that I had to change it.

MAY: There was a very good review by Michael Woods in the Times Literary Supplement. It was a review of a number of your books when a whole lot of your paperback books came out in Britain and yet he said that tenderness was a thing you couldn’t do. I thought that in Killshot you actually get round that very well. His review came out in 1985, and by the time you publish Killshot, that relationship between Wayne and Carmen has great tenderness in it.

LEONARD: That was ‘89.

MAY: I liked that stuff was where Wayne goes into his tales of the riverbank, when the ironworker, it’s almost the boy’s aspect. He finds a whole new set of toys on the river and almost a whole new terminology for him.

LEONARD: He likes that big stuff, thousands of tons. When I did his fantasy scenes up on the structure, when he does his fantasy, those are possible ways the story could have developed, directions that the reader might be thinking of. So, as soon as he has fantasized those things, they’re no longer possible. And then the reader might wonder, well what’s gonna happen with him?

….

MAY: Moving away from your novels for a moment, I’d like to talk about the non-fiction that you’ve written. Can you tell me a little about writing the preface to the book on Detroit? [Balthazar Korab, Detroit: The Renaissance City, 1989].

LEONARD: It took me about three weeks to write two thousand words. Because it’s not something that I had an urge to write. I had no desire to write it. The only reason I did it was because the photographer’s a friend of mine. Then I had to decide, What do I think about Detroit? I had to do some research on its history, and to realise when I think of this city fondly at all it goes back to a time in the 30s and 40s, riding a street car downtown. By the late 50s that was all gone. It had changed completely. It was difficult. I get asked to write non-fiction a lot by magazines and newspapers and I have to explain to them, It’s not what I do. I’m not going to get my sound when I do that. My sound is a non-sound. My sound is the sound of the characters, not me. I don’t want to hear me. I don’t want to see me in there. I don’t know why they don’t understand that in the books I’m not there. I would have to have one of my characters write the piece on Miami or whatever.

MAY: In the case of the book on Detroit, you’re a local celebrity. You’re in a list of things that represent Detroit in this weekend’s Free Press along with the Ford factory. You’re a local identity. You say that Detroit all changed in the 50s. What sort of changes occurred?

LEONARD: The fact that 700,000 people left town and moved out to the suburbs. I think at first because assembly plants moved out. Automotive assembly plants were located all around the country rather than just here. It just became easier to assemble and move around the finished product. I suppose it comes down to foreign competition, especially the Japanese, that the automotive companies here misjudged it. And finally it’s too late. It’s the same thing that’s been happening in large industrial centers all over the United States where worldwide competition beats us in making steel and producing automobiles. We’re not the leaders anymore. Oh, we still produce more cars than anybody but not to the point where we can be cocky about it. I don’t know, everybody doesn’t work in the auto plants but there are the related industries, of course. In Hamtramck, though, there were 40,000 people worked in Dodge-Main in three shifts. That’s a lot. That was probably half the working people in the town. So then they tear that down. Dodge-Main is razed and replaced with a little Cadillac assembly plant that’s full of robotics and it employs maybe 3,000. I don’t know what happened. Best restaurant in downtown Detroit closed last week. London Chop House. It was good. We were there a couple of weeks before it closed. I’d always thought that it was the best restaurant in town. No question about it. I think it just didn’t have the business. People are afraid to go downtown. And I’m sure that you can go there safely. You drive up to the place, somebody takes your car, you walk in, y’know? But they don’t have the lunch trade they used to have because there aren’t as many people in the office buildings downtown. Doubleday bookstore closed on Saturday. There’s nobody downtown. Hudson’s department store and that was it. That was the reason to go downtown. Get on a street car and go down. If you wanted to go to Windsor, just for something to do, you’d ride on the ferry.

MAY: It’s closing down now but what was it like before this? It’s obvious to anyone what downtown Detroit is like now. It’s so easy to experience. You just go down there and there’s no one about. What was it like before the change, back in the 50s?

LEONARD: It was alive. It was a vibrant, big city downtown with a lot of cars and streetcars and buses. In the blocks around Hudson’s department store, it was always crowded. You came up Woodward about three miles from downtown, you came to Grand Boulevard, Fisher Building off to your left a couple of blocks, and five more blocks north of there is where I lived through most of the 30s. And then another ten blocks north of there, in Highland Park, I lived in an apartment building. And then a couple of more miles out to Six Mile Road, when I was going to University of Detroit I lived in an apartment building there by the park. Then two more miles to Eight Mile Road was the next place that I moved when I was married the first time. Followed by Twelve Mile Road. Then we came out to Birmingham in ‘61. That’s from Twelve Mile to Fifteen Mile. Then Joan and I got married in ‘79. I like the city. I used to go to black clubs a lot. That was in the late 40s when I was going to school. I’d go to black dance clubs all the time and some nights I might be the only white guy in there but usually there were a few others. And there was no problem.

MAY: What sort of people used to play there?

LEONARD: Let’s see. There would be small jazz groups up on bandstands behind the bar. In the 40s, when I was in high school, I used to go to Perry Lanes Theatre in the afternoon sometime after school or in the evening to hear the big bands. And they were all black bands in the Paradise. They’d go from the Paradise to the Apollo in New York.

MAY: Do you still listen to jazz?

LEONARD: In my car, I have the radio set on a jazz station.

More extracts from Anthony May’s Elmore Leonard interviews will appear all week. The complete 65-page interview is available in Contrappasso issue #2, available in Paperback, Kindle Ebook, or other Ebook formats @ Smashwords.

ON RUM PUNCH, AND POINT-OF-VIEW

from ‘Doing What I Do: An Interview With Elmore Leonard’ by Anthony May (Contrappasso #2, December 2012)

Dates: 1st-3rd July, 1991

Location: Elmore Leonard’s home in Birmingham, Michigan. The interview took place in Leonard’s study across his writing desk.

MAY: On dialogue, I came across a piece where crime writers were asked to name their ten favourite books and they had all these lists, and you put down just one book, George V. Higgins’s The Friends of Eddie Coyle (1970). Dialogue is outstanding in that book, and there are a couple of things that I’ve wondered about in relation to that. What does dialogue do that other forms of description can’t? One of the things that I like in your work is the way you extend certain points of view by way of dialogue, you present a character through dialogue, and then you continue it in description, in a very productive way.

LEONARD: Exactly. I don’t know if I mentioned that in the documentary [Mike Dibbs’s Elmore Leonard’s Criminal Records (1991)], but once I decide the point of view of a scene, then that character’s sound will permeate the narrative, will continue on through, because everything you see in that scene is from that character’s point of view and you won’t know what anybody else is thinking until you come to a place on the page where I’ve skipped down a few spaces and got into someone else’s head. And it could be in the middle of a dialogue situation, a scene, where I do it is beside the point but I won’t mix up points of view. I’m a stickler for that because I think I do so much more with it than most writers. With most writers it’s a case of, here’s the scene and the people are talkin’ and then you’re back into the viewpoint of this omniscient author again. I want to keep it down there. I want to keep it in the story.

I was at a Santa Barbara writers’ conference a couple of weekends ago, and I listened to the students, reading. And they all use adverbs, ‘She sat up abruptly.’ And I tried to explain that those words belong to the author, the writer, and when you hear that word there’s just that little moment where you’re pulled out of the seat. Especially by that sound, that soft L-Y sound. Lee. So often it doesn’t fit with what’s goin’ on, y’know. I mean, if a person sits up in bed, they sit up in bed. You don’t have to tell how they sit up in bed. Especially with what’s goin’ on. In this instance, she sat up in bed ‘cause she hears a pickup truck rumbling by outside very slowly and she knows who it is. So you know how she sat up in bed. And in her mind she’s saying, ‘It’s that fuckin’ pickup truck’. She knows it is. And then there’s another, say, half a page or so of inside the character’s head and the phone rings. She gets out of bed and feels her way over and almost knocks a lamp down. And she passes this stack of self-help books, on the desk, and picks up the phone. And I suggested to the young woman who wrote this, ‘Save the fuckin’ pickup, drop the fuckin’ adverb, and put it with the self-help books and it’ll say a lot more about your character.’ See, it’s little things like that. The contrast works better.

MAY: I think that thing of not having a character working like that ‘I’ point of view all the time, by shifting to third person, the way you use that technique of point of view…

LEONARD: Gets a first person sound.

MAY: Yes, it gives a lot of license to that.

LEONARD: The trouble with first person is that you’re so limited.

MAY: Your mentioning self-help books in that young woman’s writing made me think of what seems a recurrent theme in your writing, the different things people use in order to make sense of their circumstances. Way back in 52 Pickup (1974), the Harry Mitchell character is in this situation and all he has is a set of management techniques by which to understand a kidnap and a killing. He has these management seminars, that’s the only thing he knows to use to help organize himself to get through this.

LEONARD: Yeah well, I don’t remember that in detail, but I remember that there was a parallel between the situation in his plant, with the slow-down, and what was happening in his personal life.

MAY: On that idea of characters who do or don’t fall back on failsafe devices for helping themselves, I really liked that reference in the [documentary] to handwriting analysis where Carmen in Killshot (1989) sorts herself out by straightening up her l’s or something like that.

LEONARD: And I believe that could work. You can change your handwriting and improve your personality or your mental state, your attitude. Because you just tell yourself that this is what you’re doing, that’s half of it, y’know? So when she starts writing upright, she picks herself up. But she won’t [analyse] her mother’s [handwriting] because there’s nothing good to say.

MAY: On point of view and the practice of extending point of view from dialogue into those descriptive passages which follow, I’ve always thought that must be very difficult to translate into film. Have you thought how to get around that or is that just a filmmaker’s problem?

LEONARD: Yes, it’s a filmmaker’s problem and, no, because the thing which makes my stories, my books, the style, and the references that are made using this point of view, are not visual. You lose all that. By the time you take these 359 pages down to 110-120 page script, all of this stuff’s gone. Or, most of it.

One example of really using point of view in this way is in Rum Punch [1992]. Max Cherry, the bail bondsman, is on the phone when this black guy comes into his office and I start out with just this much as Max’s point of view:

Monday afternoon, Renee called Max at his office to say she needed twelve hundred and fifty dollars right away and wanted him to bring her a check. Renee was at her gallery in The Gardens Mall on PGA Boulevard. It would take Max a half-hour at least to drive up there.

He said, “Renee, even if I wanted to, I can’t. I’m waiting to hear from a guy. I just spoke to the judge about him.” He had to listen then while she told him she had been trying to get hold of him. “That’s where I was, at court. I got your message on the beeper… I just got back, I haven’t had time… Renee, I’m working for Christ sake.” Max paused, holding the phone to his ear. He looked up to see a black guy in a yellow sport coat standing in his office. A black guy with shiny hair holding a Miami Dolphins athletic bag. Max said, “Renee, listen a minute, okay? I got a kid’s gonna do ten fucking years if I don’t get hold of him and take him in and you want me to… Renee.”

Max replaced the phone.

The black guy said, “Hung up on you, huh? I bet that was your wife.”

The guy smiling at him.

Max came close to saying, yeah, and you know what she said to me? He wanted to. Except that it wouldn’t make sense to tell this guy he didn’t know, had never seen before…

The black guy saying, “There was nobody in the front office, so I walked in. I got some business.”

The phone rang. Max picked it up, pointing to a chair with his other hand and said, “Bail Bonds.” (pp. 11-12)

[There is a slight variation between the manuscript and the published text.]

So I saved what his wife said to him until a little bit later when somebody else comes in. ‘Cause he’s not gonna tell this guy. But now it’s this guy’s point of view.

Ordell heard him say, “It doesn’t matter where you were, Reggie, you missed your hearing. Now I have to… Reg, listen to me, okay?” This Max Cherry speaking in a quieter voice than he used on his wife.

This is now Ordell’s point of view, see.

Talking to her had sounded painful. Ordell placed his athletic bag on an empty desk that faced the one Max Cherry was at and got out a cigarette.

So then there’s all this from Ordell’s point of view (a little description, then Ordell overhearing Max’s conversation):

[Max] could be Eyetalian, except Ordell had never met a bail bondsman wasn’t Jewish. Max was telling the guy now the judge was ready to habitualize him. “That what you want, Reg? Look at ten years instead of six months and probation? I said, ‘Your Honor, Reggie has always been an outstanding client. I know I can find him right now…’“

Ordell, lighting the cigarette, paused as Max paused.

“‘…outstanding on the corner by his house.’“

Listen to him. Doing standup.

“I can have the capias set aside, Reg…” (pp. 12-13)

So you see this exchange, it’s hard to separate ‘outstanding’ and I’ve put it in the wrong place, that’s why you see that. So you’ve got two different things going on at the same time, in that use of point of view.

MAY: Do you try to develop that as a specific technical interest as you write or is it more an intuitive sense of how the writing is working?

LEONARD: It just happens. I come at it and use it. I like the idea of levels of things going on. To try and do that. Then you come to the end of the scene, he wants to bond a guy out. Costs ten thousand dollars, and he says:

[Ordell] stopped and looked back. “I got one other question. What if, I was just thinking, what if before the court date gets here Beaumont gets hit by a car or something and dies? I get the money back, don’t I?”

*

What he was saying was, he knew he’d get it back. The kind of guy who worked at being cool, but was dying to tell you things about himself. He knew the system, knew the main county lockup was called the Gun Club jail, after the street it was on. He’d served time, knew Louis Gara and drove a Mercedes convertible. What else you want to know? (p. 17)

So now we’re back on Max’s point of view.

More extracts from Anthony May’s Elmore Leonard interviews will appear all week. The complete 65-page interview is available in Contrappasso issue #2, available in Paperback, Kindle Ebook, or other Ebook formats @ Smashwords.

To kick off Elmore Leonard Week, here’s our man Anthony May on interviewing Elmore Leonard in Detroit in 1991. Thanks to Gregg Sutter, Elmore’s researcher, for digging up the photo. This article was originally published in Contrappasso Magazine, issue #2.

GOOD TIME CRIME: TALKING WITH ELMORE LEONARD by ANTHONY MAY

Back in 1991, I had the good fortune to sit down with Elmore Leonard in his Michigan home during the hot summer and lead up to the fourth of July celebrations that would be the first since Operation Desert Storm, quite a big thing around Detroit. I was there to talk to him about his books but he is an intelligent man and sees the connections in things so the conversation moved around. He had just finished the manuscript of Rum Punch and maybe he felt like a chat. In the end we spent quite a few hours together over three days trying to make some connections across the stories, books and films that comprise his long career. He was very generous with his time and opinions and I remain extremely grateful for the access and the insight. A couple of years later, when he was in Sydney, we sat down again and continued the conversation. The interviews that follow record those conversations and, hopefully, give another way into the books that have delighted so many.

The book that was about to come out that summer was Maximum Bob, the story that introduced characters like Judge Bob Gibbs’ wife, who channels a black slave girl who had died one hundred and thirty years before. In the books leading up to this, he had begun to foreground characters who were free and loose in their own way and in ways that were not just due to their involvement in crime. And this was coming to mark a kind of maturity in his writing that began with the shift from the western to the contemporary crime novel and the necessity to deal with what he calls “contemporary scenery”, and, from there, the requirement to take on board contemporary character. He was doing it at a novel a year, a pace he took up in the seventies and kept working at through the nineties.

It had been a long road from his early days as an advertising copywriter in the 1950s when he was writing stories for Argosy, Dime Western and the other short story and western magazines in his spare time. Movies were based on his early stories ‘Three-Ten To Yuma’ (3:10 To Yuma, 1953, D: Delmer Daves) and ‘The Captives’ (The Tall T, 1957, D: Budd Boetticher). He eventually hit the slicks, like Saturday Evening Post, but he had entered the game too late and the time of that style of publishing was coming to an end. He published western novels along with the stories but without the movies to take up the property there was diminishing joy in this field. Fittingly, it was a western film, Hombre (1966, D: Martin Ritt) from Leonard’s 1961 novel, the only novel of his to feature a first person narrator, that allowed him to make a change. The film, starring Paul Newman, Richard Boone and Diane Cilento, was a success, because of Newman, of course, but also because, like a number of big screen westerns of the time, it was a revisionist history of the west. This was something that had been consistent in Leonard’s westerns—not so much rewriting the history of the period as readdressing the idea of character in the west. There were never good guys and bad guys, white hats and black hats, good baddies and bad goodies, nor the usual array of stock western characters. There were interesting characters, funny characters, mean characters and ones that slid back and forth. It was his main concern back then and it continues to this day.

The change to the contemporary novel didn’t happen overnight. He published some novels through the sixties and early seventies but it was the movies again that really brought him back into the game. The original screenplay for Joe Kidd (1972, D: John Sturges) was Clint Eastwood’s first film after Dirty Harry (1971, D: Don Siegel). That led to Eastwood requesting another screenplay from Leonard, which turned out to be Mr. Majestyk (1974, D: Richard Fleischer). Eastwood passed on the project (he preferred the idea of an artichoke farmer to a melon grower) but with Charles Bronson in the lead, it was another moneymaker. By the mid-seventies, the novel projects were coming into line once more—52 Pickup (1974), Swag (1976), The Hunted and Unknown Man #89 (1977)—and he was into that one-novel-a-year output cycle. But with rewards this time around. All these novels were being optioned as movies. Alfred Hitchcock picked up Unknown Man #89 and the rights remained with him until he died. Sam Peckinpah had City Primeval (1980) but it never happened. Nonetheless, he had gone from an advertising copywriter who wrote western stories part-time to a novelist who sold every book that he wrote into hardback and into the movies. This was success. Perhaps just as important as the success, this was fun. It’s difficult to read an Elmore Leonard novel and not realize that we’re all having fun, reader and writer alike.

All readers come to the progression of Elmore Leonard’s books at a different point. Thanks to the loan of a paperback from a friend, I’d begun with Glitz (1985) and, like a lot of readers, I began filling in the time between new releases by reading the back catalogue. Publishers know this happens and that’s why there are so many different Elmore Leonard paperback editions of the same book. As he has shifted publication houses over his career, there has been a tendency for publishers to buy the back catalogue and rerelease the older novels knowing that they will still sell. And there is value in picking up the back catalogue that doesn’t just accrue to the publisher and Mr. Leonard.

There is, in the progression of novels since the mid-seventies, a development of style that is particular to Elmore Leonard and intriguing for the reader. When he gets to the contemporary novel, he begins to experiment with ways of telling stories that suit his character-based concerns. As he says in the interviews, he had work to do in moving his storytelling into the present. When you write about the Arizona of one hundred years before, there are not a lot of people around to point out your mistakes, although he was pretty rigorous about using his reference books to keep those stories in line. But when you live and write in nineteen seventies Detroit, Detroit is just outside your door. And so is your reader. So if Temple Street doesn’t cross Woodward Avenue at the right place, people know. And they let you know. And if the young hipsters are using last year’s hipster talk, people know. And they let you know. And so the world of the book has a much more demanding relationship with the world of the reader than it ever had in the western. But it didn’t take him long before he was having fun with it.

The movies of the early seventies had signalled a shift for him. Joe Kidd was about an ex-bounty hunter who was dragged into a brawl between a wealthy landowner and a Mexican revolutionary leader. Mr. Majestyk was about a melon farmer who stood up alongside his Mexican field workers against the mob. Vince Majestyk was a Vietnam veteran but that wasn’t the big thing. He signalled a move for Leonard, to finding his lead characters in everyday roles, characters who might just get caught up in something criminal or generally bad. In 52 Pickup, Harry Mitchell runs a manufacturing plant; in Swag, Ernest Stickley, jr., is a down-on-his-luck cement truck driver before he gets eased into armed robbery; in Unknown Man #89, Jack Ryan is just looking for any old job when he gets taken on as a process server. Ordinary guys get caught up in the grey areas of ethical life and that is the type of thing that Leonard loves.

So piece by piece, the lead characters come into view, along with the modern world in which they live. The nice thing for Leonard is that his focus on the ordinary and the extraordinary cuts both ways. His ordinary folk become revealed as just as wild as the sociopaths and the sociopaths reveal their own concerns with the everyday. This became the Elmore Leonard playground in which we all had fun. At the same time he was shaking off those genre constraints that had shackled his westerns. Moving to the contemporary crime novel, it was inevitable that a certain amount of genre limitation was going to carry over. But the eighties put an end to all of that. In 1980, he published his first book with Arbor House, City Primeval: High Noon in Detroit. His publisher was Don Fine, who had made it clear that the first job of selling Elmore Leonard novels was to sell Elmore Leonard. The title of the book was a play on Leonard’s past as a western storywriter as much as it messed with the idea of the gunfight in the modern day. And the book is full of this type of play. In one scene, Raymond Cruz, the police detective at the centre of the story, manoeuvres a fellow officer into the home of Mr. Sweety, a local club owner, drug dealer and armed robber, to see a photograph of Jesus. The colleague thinks it might be Leon Russell but doesn’t give it much credence as Jesus. No-one but Raymond is surprised that it is a photograph of Jesus. No-one, especially Leonard, actually points out the incongruity of having a photograph of Jesus, as I just did. This is the modern world, Leonard-style—no-one is at that level and no-one tries to explain.

Modern world Detroit, when I was there in the early nineties, was trying to get on its feet. There weren’t many signs of renewal at that stage. There had been the Renaissance Centre that had been built at the end of the seventies and completed in the eighties but was starting to look a little shabby. That’s the site of the George Clooney-Jennifer Lopez bedroom scene in Out Of Sight (1998, D: Steven Soderbergh, screenplay Scott Frank, novel Elmore Leonard) although General Motors had renovated and rebadged the complex by then. There was the people mover, an elevated light rail project, that had opened just a few years before and was designed to get souls around the downtown safely and efficiently. Gregg Sutter, Leonard’s researcher, told me that it was commonly known as the people mugger but I was never clear whether that referred to the pricing or the unachieved ambition of passenger safety. It also had ‘The Fist’, officially known as the ‘Monument to Joe Louis’, I believe, but let’s call a fist a fist. Over seven metres of arm and fist, the arm and fist of Joe ‘Brown Bomber’ Louis, suspended in a pyramid like a battering ram at Hart Plaza. The sculptor, Robert Graham, got it right. Just like Joe Louis, not pretty but very powerful.

So a few things were happening in this tired, divided city, but downtown entertainment tended to be a couple of extremely well-lit streets in Greektown. The jewel in the crown of the renovations was the recently restored Fox Theatre on Woodward Avenue. As a movie buff, I was in awe of the Fox because it was one of the great movie picture palaces of the 1920s. It was the largest on the Fox chain. As a music buff, I was in awe of the Fox because by the 1960s, after the run down of the picture palaces, it became home to the great Motown and other music revues. Most everyone I listened to, growing up, had played here. Gregg Sutter took me to a benefit screening that was to support the renovations that had taken place. I was going to see a brand new 70mm print of Spartacus (1960, D: Stanley Kubrick, starring Kirk Douglas, Laurence Olivier, Jean Simmons) but I was totally unprepared for the building. I knew it was big and seated around 5,000 but I didn’t know the lobby was six floors high. I didn’t know that a picture palace was a palace.

So the city, in its immediate pre-Eminem days, was working at change but there were few signs of that change taking hold. At least that’s how it felt when I stopped at a traffic light outside Hudson’s Department Store on Woodward, not yet out of downtown, about ten in the morning, listening to some country music on the radio, and looked to the side to see two police spreading two young black men over their car. The good feeling from the Fox melted into the clichés of an American cop show and I went on to sit down for another session with the man who had himself become one of Detroit’s renewal figures.

There’s a difference between being a writer who lives in Detroit and a Detroit writer. Detroit has well and truly claimed Mr. Leonard as its own, but, then again, so has South Beach, Florida. But this was where he really made his name. Unlike the westerns, where he started too late, Detroit was growing into a new skin just as he was trying to get it all down on paper. The renewal hadn’t started and he was prospecting in some very rough ground for a while there. One of the things that helped move it along was the chance to ride with the Detroit police in 1978. The Detroit News Magazine asked him to do a feature article on the police and he found such an abundance of material that Squad Seven of the Detroit Police Department Homicide Section became his posse for two and a half months. This was the accelerator that brought Detroit into perspective. Seeing Detroit from this angle was to allow him to get under the skin of this city and, very important to Leonard, keep his facts straight.

Riding with Squad Seven did more than give him access to the Detroit demi-monde. It gave him time to study the contemporary scenery that had become so important to him. If the cops made their coffee in a Norelco coffeemaker, he wanted to be sure that he had the right brand of coffeemaker, and if the interview room for the murder squad had gray paint on the walls and not light blue, he wanted to know. It was not about being obsessive. There was something about getting that contemporary scenery right that led to getting those contemporary characters right. He never really articulated it to me in detail but it was there in the books—pay attention to the characters, where they live and what they do. The clues to who they are are all around them but you might not pick it on the first pass. Squad Seven sharpened his eye.

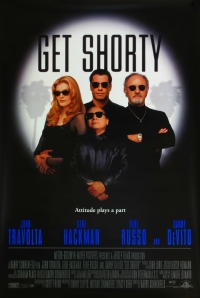

The result of the serious attention he gave to Detroit was returned when he became a figure that the city claimed as its own. He started to crop up on the magazine lists of ‘Most Famous Detroit’ celebrities that all cities run about their homegrown. But, like the local press anywhere, they are always slightly insecure and so it all began after Newsweek (22 April, 1985) ran his picture on the cover when Glitz made the bestseller list. Don Fine was right—sell the man and then you can sell the books. The Newsweek article was very complimentary and passed on the ‘overnight success after twenty years’ rhetoric that had been running for a couple of years. But seeing your face on every newsstand in every place you go, if only for a week, has to play with your head. Leonard had the last laugh when, in the movie of Get Shorty (1995, D: Barry Sonnenfeld, starring John Travolta, Gene Hackman, Rene Russo and Danny DeVito), DeVito’s character is splashed all over the newsstands dressed as Napoleon as publicity for his latest film (another famous shorty). Leonard likes to use what he has and the sensations that come with major fame had to find a way into his work somehow.

Eventually you begin to wonder what doesn’t get into the work, or at least what the filter might be. It certainly isn’t about going out into the world, finding the biggest nut jobs to write about and getting the names of the cars right. There’s something going on in a Leonard novel that brings all this material together—contemporary character, contemporary scenery, contemporary nut job—and, when the story has had its play, we feel that we know more about something. Even if we don’t know what it is. Maybe he doesn’t know either. He is insistent about not having themes (“I don’t have themes”) but pretty tight-lipped about what he does have. He’s a very amiable man but much more attuned to listening to you than revealing things about himself.

It isn’t difficult to get down to one level. He doesn’t work with themes—he works with character. He writes stories that are based on the vagaries of character and the places where those little hiccups of personality take his characters when they get into situations that are not clearly defined in their everyday lives. It’s those grey areas that he likes so much (“Some things that my people do are illegal but not necessarily immoral”). To get at those characters, however, you have to know something about the world that they live in. To get a handle on the first, you have to know about the second. Back in the day, as they say, Leonard would have known a bit about the second. In the fifties, he was an advertising executive in a major city, keen on jazz (“In my car, I have the radio set on a jazz station”) and the jazz clubs that flourished in Detroit, lots of nightlife, lots of drinking, lots of everything. This was the social scene that eventually gave us Motown. All those musicians that they make documentaries about today would have been recruited from the clubs that Leonard would have frequented. It was probably quite a life for a while.

He certainly wasn’t living that life when I met him. He had been a non-drinker for quite some time but, when we met, had recently given up smoking. It took me a while to realise, as we talked across his writing desk with an enormous ceramic ashtray between us, that as much as I was encouraging him to fill my tape with stories, he was encouraging me to fill the ashtray. He had a very nice large house with lovely grounds and a very comfortable room in which to write. Access to the life came from research these days. In part, that’s what riding with Squad Seven had done for him, tuned him into how to research the modern day life. And that’s what Gregg Sutter helped him with.

It would be wrong to overstate the usefulness of having a researcher like Gregg Sutter, and he would be the last person to do that, but it is clear that it helps. Sutter came into the picture around the time of the writing of Split Images (1981). He had met Leonard and written about him earlier for Detroit Monthly magazine. Leonard invited him to do some research on material that went into Split Images. They clearly get along and Sutter’s involvement has grown with each book. Today he runs Leonard’s official website amongst other things. Sutter is an extremely enthusiastic and energetic man. Like Leonard, he is very generous but unlike my time with Leonard which was spent, for the most part, sitting on leather furniture talking back and forth, my time with Sutter was spent in his car riding around Detroit looking at the real locations of where the books were set from Police Headquarters at 1300 Beaubien to Lily’s Bar in Hamtramck. Hamtramck is just north of Poletown and stuck between the intersection of the Chrysler Freeway and the Edsel Ford Freeway. (It’s impossible not to love these Detroit names.) Sutter’s a man who’s always on the move. He even managed to film the punk band playing at Lily’s (the singer was a friend of his) whilst showing me around the place.

The research that Sutter provides is important but, as the interview shows, the sifting process that Leonard puts the material through is more important. He has boxes and boxes of material and, as we looked through them together, it became clear that what he found was triggering more than just memories. Everything is a potential springboard for an idea and that is probably a lot of what separates the researcher from the writer. It begs the question of why Leonard stays with crime but he was very clear on that: “It in itself is exciting so that you can do it low key, be calm and quiet about it.” Being calm and quiet is a lot of what Leonard does. The characters may well be outrageous and the situations that they find themselves in are generally extreme but their reactions normally come from the range of options that most of us experience. A good example is Elvin Crowe, brother to Roland and uncle to Dale, all Leonard familiars from different books. In Maximum Bob, Elvin tracks someone for shooting Roland. When he finds him sitting in a lavatory stall, he shoots him. And the police pick him up. When Elvin finds out that he has shot the wrong man he wants his charge diminished because, well, it was an accident, wasn’t it? No, we don’t go around shooting strangers, but we do feel miffed when we get taken to task for an accident. Leonard gets this and he does it low key.

Low key is very important because you never read a lot of Elmore Leonard in his books. In his now famous rules for writers, he always advocates avoiding those things that let you know that there is someone actually writing the book, like adverbs. It comes back to training. He hears the dialogue as it goes on the page and that is an inordinate strength for any novelist. That’s one of the things that he got from Richard Bissell, the only American novelist since Mark Twain to hold a pilot’s license for the Upper Mississippi. But there’s more to his novels than just dialogue. He has to deal with narrative and, in dealing with narrative, he developed an approach that marks him out amongst modern day writers. By the time of the mid-eighties, he had developed a narrative style that was his own and one that allowed him to experiment with, and sometimes improvise on, character.

By the time that Elmore Leonard had become a bestselling author, you just didn’t read him in his books. He wasn’t there. He’d put those comparisons with the old private eye novels well and truly behind him but they are good for helping us realize what is so special about him. In the old Raymond Chandler novels, the private dick is always in the action, taking you from clue to clue and from scene to scene. It had its benefits. It maintained an intensity and it gave the reader a strong character to lead him or her through the vagaries of the urban underworld. But it was very limiting. You couldn’t get away from that character. Leonard broke that grip without having to move to the overview of a narrator that could calmly direct you from scene to scene. Leonard began to experiment with narrating scenes from the point of view of individual characters but without making it explicit who was doing the narrating. The effect was dynamic. It allowed readers to fathom their own way through the story, intuiting who was colouring the scene as they went along.

There was nothing new about this. Flaubert had been doing it in France over a hundred years before, but Leonard was doing it here and now and with the nut jobs of Detroit and Miami. He doesn’t always use it just to colour scenes and hide his own presence. There is a section in Out Of Sight (1996) where Jack Foley is being driven around the empty Detroit car plants by his buddy, Buddy. Buddy is telling Jack about the time when he worked there. Jack is thinking about the sexy female cop that he had been locked in a car boot with down in Florida. The reveries intercut and, technically as well as aesthetically, it is one of the most marvellous sequences in contemporary popular fiction. On top of that, Steven Soderbergh did a great job of filming the sequence in the movie with George Clooney and Ving Rhames.

When we got around to talking about writers that he admired, Leonard was quick to point out the other Miami master, Charles Willeford. But the interesting thing about Willeford was that he never really did make it and that was important for Leonard. As he says, “My contention is that once you’ve established yourself then you can do anything you want.” There have been some things that he has gone back on. I asked him about writing short fiction again and he said that he couldn’t do that anymore. But he did go back to that. By the mid-nineties, a few short pieces were coming out here and there but, to be fair, that was more along the lines of using fragments and bits and pieces of things that might well have come from other novels that he was writing or scenes with characters from past novels that he had to cut.

He stayed away from writing for the movies and that was a good thing. There’s a lot to be said for a volume of work and one of the nicer things about rereading Elmore Leonard is that development of craft, the way he works so hard to get out of the space between the reader and the story. You can forget, if you are not careful, that it is his imagination that you’re playing around in.

I can only repeat my gratitude for his generosity at the time. Detroit is an interesting city but it is made much more interesting with Elmore Leonard as a guide. I took in the fourth of July celebrations before I left town and as I prepared to drive to Toronto the next day I read the paper with a cup of coffee. There had been a number of incidents amongst the general exuberance of the celebrations. Amongst the arrested was a pair of twins, Cassandra and Cassondra, two teenage girls who were going around causing a bit of mayhem. When they were arrested, they admitted that they only did this sort of thing because they liked to hang with the cops. Maybe I was wrong all along. Maybe in a town like that you just have to look out of the window and write down what you see. Or maybe not.

I would like to acknowledge Noel King for his work on a preliminary edit of these interviews.

It’s Elmore Leonard Week at Contrappasso. For the next seven days we will be celebrating the life and career of the legendary crime writer.

Contrappasso issue #2 features Anthony May‘s never-before-published, 23,000-word, 65-page interview series with Elmore. It’s surely the most expansive Elmore Leonard Q&A ever. We’ll be running selected extracts this coming week. Elmore on point-of-view. Elmore on the city of Detroit. Elmore on research. Elmore on the movies. And Elmore on the birth of Raylan Givens.

So stay tuned for the best kind of Dutch Treat.